Guide to Non-Ferrous Metal Forging Process

In modern industry, non-ferrous metals and their alloys are widely used, appearing everywhere from aerospace to automotive manufacturing, from electronic devices to medical instruments. As an important part of non-ferrous metal processing, forging plays a vital role in improving material performance and meeting the demands of various complex working conditions. This article will explore the forging processes of non-ferrous metals, focusing on the forging characteristics and technical points of aluminum alloys, magnesium alloys, titanium alloys, copper alloys, and rare metals, helping readers gain a comprehensive understanding of this field.

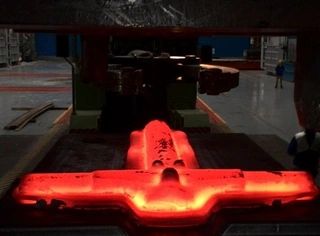

Aluminum Alloy Forging Process

In the field of non-ferrous metal forging, aluminum alloy forging occupies a very important position. Aluminum alloys are widely used in aerospace, automotive manufacturing, electronics, and other industries due to their excellent strength, corrosion resistance, and workability.

1. Forging Methods

Aluminum alloy forgings are diverse, including open-die forging, die forging, upsetting, roll forging, and hole expansion. Open-die forging is relatively flexible and can produce forgings of different shapes and sizes as needed, suitable for single-piece or small-batch large forgings. Die forging can produce complex shapes with high dimensional accuracy, widely used in fields such as automotive and aerospace where component precision is extremely demanding. Upsetting is mainly used to thicken the billet to increase its cross-sectional area, commonly used for manufacturing bolts, shafts, and similar parts. Roll forging involves deforming the billet with a pair of rotating rolls, suitable for producing long shaft parts. Hole expansion enlarges the billet's hole diameter, used for producing tubular parts or complex forgings with through holes.

2. Temperature Control and Deformation Resistance

Aluminum alloys, especially high-strength aluminum alloys, experience a sharp increase in deformation resistance as temperature decreases. This means that during forging, to reduce deformation resistance, final forging must be performed at a relatively high temperature with a larger deformation degree. In general, the initial forging temperature of aluminum alloys should be controlled within an appropriate range to avoid overheating, while the final forging temperature must not be lower than the recrystallization temperature, otherwise deformation resistance and work hardening will increase. For example, for some high-strength aluminum alloys, the initial forging temperature may be around 450°C, and the final forging temperature should be kept above 350°C. Precise temperature control can effectively reduce energy consumption during forging while ensuring forging quality.

3. Billet Selection and Treatment

Billets for aluminum alloy forging mainly include cast ingots, forged billets, and extruded billets. Cast ingots used for open-die forging or as billets must first undergo homogenization to eliminate internal composition segregation and uneven structures. Homogenization is usually performed at high temperature, allowing the strengthening phases in the alloy to dissolve fully, achieving a uniform structure. Forged billets are mainly used for large die forgings; their structure is relatively uniform and can withstand significant forging deformation. Extruded billets (such as rods or profiles) are suitable for die forging but require high-temperature homogenization treatment before use to eliminate residual stresses and structural defects generated during extrusion. Extruded billets also need repeated upsetting to further improve their structural properties. For high-performance forgings, the extruded billets should be turned to remove surface defects, ensuring surface quality and internal structural integrity.

4. Billet Cutting and Forging Lubrication

Aluminum alloy billets are usually cut using saws, lathes, or milling machines; sometimes shears are used, but abrasive wheel cutting must never be used, as it generates excessive heat, which may cause surface cracks or oxidation layers, affecting subsequent forging quality. During forging, aluminum alloys have a high friction coefficient and poor flow at high temperatures, making them highly sensitive to cracking. To reduce this, the contact surface between the billet and tools must be lubricated. Common lubricants include a mixture of water and gelatinous graphite; for complex die forgings, a small amount of soap is added to improve lubrication. Another option is a mixture of machine oil and graphite, typically containing 80%–90% oil, which can be reduced to 70%–80% for large or simple die forgings. Proper lubrication effectively reduces friction, minimizes surface scratches and cracks, and improves forging surface quality.

5. Finishing Treatment

Finishing work for aluminum alloy forgings mainly includes trimming edges and removing folds, cracks, and flaking. Except for ultra-hard aluminum alloys, most aluminum alloy finishing is done in the cold state. For large die forgings, sawing is generally used due to its high cutting precision, ensuring edge quality. Finishing removes excess material and surface defects, achieving the required dimensional and shape accuracy, preparing the forging for subsequent processing or use.

Magnesium Alloy Forging Process

Magnesium alloys, with their light weight, high specific strength, and good vibration-damping performance, are widely used in aerospace, automotive, and electronic products. However, their forging process is relatively complex, requiring strict control of forging temperature, deformation rate, and lubrication conditions to ensure final product quality and performance.

1. Forging Methods and Deformation Characteristics

Magnesium alloys have good plasticity, but it is strongly affected by deformation speed within the forging temperature range, so forging is usually done on a press. Magnesium alloys are sensitive to tensile stress, making upsetting or flat-anvil stretching unsuitable, as excessive tensile stress can cause cracks. Simple shapes with a total deformation not exceeding 35% can be formed in one die forging. Complex shapes with total deformation exceeding 40% require two or more forging steps to avoid cracks and other defects. During forging, deformation speed and degree must be strictly controlled to fully utilize magnesium alloy plasticity while preventing unnecessary defects.

2. Temperature Control and Lubrication

The forging temperature range for magnesium alloys is generally 320–450°C. Heating should not exceed 4 hours, otherwise plasticity and mechanical properties are reduced, as the softening effect cannot be fully compensated by subsequent forging and heat treatment. To prevent cracks caused by rapid cooling when the magnesium alloy contacts a cold die, dies must be preheated to 250–300°C or higher. Common lubricants include mineral oil (such as machine oil or cylinder oil) with fine graphite powder at an 80:20 ratio, or oleic acid with paraffin at 90:10. Proper lubrication reduces friction with the die, lowers forging force, improves surface quality, and extends die life.

3. Edge Trimming and Crack Prevention

To prevent edge cracks, magnesium alloy edge trimming should be performed in the 200–300°C hot state. Hot trimming avoids cracks caused by large temperature differences during cold trimming, ensuring quality and dimensional accuracy, and provides a solid foundation for subsequent processing or use.

Titanium Alloy Forging Process

Titanium alloys are widely used in aerospace, marine, automotive, and medical fields due to their excellent strength, light weight, corrosion resistance, and high-temperature performance. Titanium alloy forging is a key step in improving mechanical properties and service life, offering high efficiency, precision, and quality.

1. Forging Methods and Deformation Resistance

Titanium alloys have sufficient plasticity for open-die forging, die forging, extrusion, and other methods. However, their deformation resistance is high and increases sharply as temperature decreases, reducing their ability to fill dies and causing die sticking. Careful control of forging temperature and deformation speed is essential to avoid forging difficulties and defects. Titanium alloys are usually forged in the α+β phase region to achieve good plasticity and lower deformation resistance. Choosing appropriate forging methods and parameters fully utilizes titanium alloy advantages and produces high-quality forgings.

2. Billet Treatment and Defect Removal

All defects on titanium alloy billets must be removed by turning or grinding. Open-die billets typically require 3–5 mm skin removal; extruded billets require 2–3 mm. Cutting can be done cold on lathes, abrasive saws, or anodic cutting machines, or hot on shears at 750–900°C. Gas cutting is strictly forbidden, as it causes surface oxidation and cracks, seriously affecting forging quality and performance. Proper billet treatment ensures surface quality and structural integrity, providing a solid foundation for high-quality titanium alloy forgings.

3. Heating and Lubrication

Heating titanium alloys requires strict control of temperature, heating rate, holding time, and furnace atmosphere. To reduce oxidation, high-temperature holding time should be as short as possible, just enough for full section heating. Forging temperatures for α and α+β titanium alloys are usually within the α+β phase region. Common lubricants include water-gelatinous graphite mixtures, heavy oil or machine oil with graphite, graphite with molybdenum disulfide, or glass coatings for high-temperature alloys. Proper heating and lubrication reduce oxidation and wear, improving forging quality and extending die and equipment life.

Copper Alloy Forging Process

Copper alloys are widely used in power, shipbuilding, and machinery manufacturing due to excellent electrical conductivity, corrosion resistance, and mechanical properties. Copper alloy forging is critical for producing high-quality products, with strict requirements for temperature, lubrication, and equipment.

1. Forgeable Copper Alloys

Forgeable copper alloys include brass, bronze, and nickel silver. For forging brass, zinc content is generally below 32%; aluminum bronze contains 8–10% aluminum. These alloys have good plasticity and forgeability, enabling production of various shapes and sizes to meet industrial needs.

2. Forging Methods and Die Preheating

Copper alloys can be forged on hammers, but increasing deformation speed increases deformation resistance, making die forging on presses preferable. Copper alloys can also be ring-rolled on hole-expanding machines for tubular parts or perforated forgings. Dies are generally preheated to 200–300°C to prevent rapid heat loss, ensure smooth forging, and improve surface and structural quality.

3. Lubrication and Die Protection

Dies must be lubricated during forging, usually with a mixture of gelatinous graphite and water or oil. Lubricants reduce friction, lower forging force, prevent adhesion, improve die life, and enhance surface quality. Proper lubrication increases production efficiency and product quality while reducing costs.

Conclusion

Non-ferrous metal forging is a complex and precise process involving multiple materials, forging methods, and strict control of temperature, lubrication, and billet treatment. Mastery of these processes improves the quality and performance of non-ferrous forgings, meeting modern industrial requirements for high-performance materials. Aluminum, magnesium, titanium, copper, and rare metals each have specific characteristics and requirements during forging, and forging methods and parameters must be chosen based on material properties and product needs to achieve optimal results. With ongoing technological advancement and industrial development, non-ferrous metal forging continues to evolve, providing strong technical support for modern industry.

Send your message to this supplier

Related Articles from the Supplier

Guide to Non-Ferrous Metal Forging Process

- Nov 06, 2025

A Guide to Non-Ferrous Alloy Casting

- Jun 27, 2025

Guide to Aluminum Alloy Forging Technology

- Nov 13, 2025

A Comprehensive Guide to Aluminum Forgings

- Jul 25, 2024

The Buyers’ Guide on Forging Components

- Dec 24, 2014

Related Articles from China Manufacturers

Guide to Non-Destructive Testing of Storage Tanks

- Jan 06, 2026

Guide to Troubleshooting of Pneumatic Ball Valves

- Feb 04, 2026

Guide to Liquid Die Forging Technology

- May 20, 2025

Guide to Nickel-Based Alloy Open Die Forging

- Dec 09, 2025

Guide to Multi-Directional Die Forging Technology

- Feb 04, 2026

Guide to Industrial Valve Repair and Maintenance

- Jan 24, 2025

Guide to Pipe Bend Manufacturing Processing

- Sep 03, 2025

Related Products Mentioned in the Article

Supplier Website

Source: https://www.forging-casting-stamping.com/guide-to-non-ferrous-metal-forging-process.html