Pipeline Erosion from Ammonium Chloride Crystallization in Catalytic Cracking Units

Abstract: This study investigates pipe perforation and leakage caused by erosion from ammonium chloride crystallization in the top circulation system of heavy-oil catalytic cracking units. By analyzing the erosion and wear behavior of salt crystallization, areas prone to perforation are identified, and appropriate preventive measures are proposed. The 180° pipe bend at the outlet of heat exchanger F203/1~2 is used as the study object, and a simulation model is established based on the Euler–Lagrange approach. The flow field and erosion behavior within the bend are simulated in ANSYS Fluent 2020 under real operating conditions. The effects of inlet velocity, salt-crystal particle size, and particle mass flow rate on the erosion rate are analyzed using the controlled-variable method. The results indicate that the middle and both sides of the outer arch wall are the key erosion zones and most prone to perforation. The erosion rate rises linearly with inlet velocity and increases sharply when the velocity exceeds 2.5 m/s. The particle size varies gradually between 0.01 and 0.07 mm, while the erosion rate drops significantly when the size exceeds 0.07 mm. The particle mass flow rate has a strong influence on erosion, with the erosion rate increasing more rapidly once it exceeds 0.09 kg/s. These findings offer a theoretical basis for the periodic inspection of vulnerable areas, the development of prevention and control strategies, the optimization of process parameters, and the scheduling of pipeline replacement. Since its commissioning in 2003, the 3 Mt/a heavy oil catalytic cracking unit at the Lanzhou Petrochemical Branch of China National Petroleum Corporation has primarily processed vacuum residue oil as feedstock. With the decline of light crude resources, the unit increasingly processes heavy, lower-quality feedstock, leading to significantly elevated levels of corrosive components, including sulfur, nitrogen, and chlorine. The chlorine concentration (0.04726 mg/L) surpasses the control limit of 0.03 mg/L, and during catalytic cracking, the abundant chloride ions readily precipitate as ammonium chloride crystals. In the previous operating cycle, erosion and corrosion from these crystals led to a perforation and leakage in the 180° bend at the outlet of heat exchanger F203/1~2 in the top-circulation reflux system, severely compromising the unit’s long-term stable operation. Extensive research on pipeline erosion has been conducted globally. Su et al., using morphological analysis and CFD simulations, showed that erosion in 30° bends is primarily caused by cutting deformation. Parkash et al. conducted simulations on bends with varying curvatures and found that erosion is most severe on the outer side of the outlet. Zhang et al., employing an Euler–Lagrange model, studied erosion in seabed water–solid mixtures and experimentally confirmed that flow velocity is a primary influencing factor. Ai Chunming et al. investigated erosion in 90° elbows using both experimental and numerical methods, demonstrating that erosion is closely linked to particle motion and intensifies with increasing slurry velocity. Yang Siqi et al., using a discrete phase model, found that in high-pressure elbows, the primary erosion zone is concentrated on the outer side of the bend outlet. However, most existing studies focus on erosion by sand or other solid particles, and predictive models for salt-crystal-induced erosion in oil pipelines remain unavailable. Addressing this gap, the study focuses on the 180° bend at the outlet of heat exchanger F203/1~2 in the top-circulation system of Lanzhou Petrochemical’s heavy oil catalytic cracking unit. ANSYS Fluent 2020 is used to numerically simulate the erosion process caused by ammonium chloride crystallization, systematically analyzing the erosion characteristics under varying inlet velocities, particle sizes, and particle mass flow rates.

1. Analysis of Ammonium Chloride Salt Formation and Erosion Mechanisms

1.1 Principle of Ammonium Chloride Salt Formation

During catalytic cracking, wax oil and residue oil are fully mixed in the feed mixer before entering the feed buffer tank. After being pumped out and heated by the slurry, the mixture enters the riser reactor. Under the high temperature and pressure of the reactor, complexes and chlorides in the mixed feed undergo cracking reactions, producing NH₃ and HCl. At high temperatures, NH₃ and HCl exist separately, but at lower temperatures, they undergo a reversible reaction to form ammonium chloride (NH₄Cl). As the oil–gas mixture ascends the fractionation tower and cools, most of the NH₃ and HCl in the vapor phase convert into NH₄Cl. Because ammonium chloride crystallizes around 142 °C, and the top-circulation draw is maintained at 145 °C while the reflux tower is at about 110 °C, low-temperature zones form in the pipelines between the draw and reflux tower and on the fractionation tower trays. As a result, NH₄Cl readily crystallizes on the trays and within the top-circulation pipelines, with a small amount accumulating on the trays and the majority carried along the pipelines with the circulating oil.

1.2 Erosion Mechanism

Erosion is a common physical phenomenon influenced by multiple disciplines, including materials science, mechanics, and tribology. Depending on the flowing medium, erosion can be classified as gas–solid, liquid–solid, droplet, or cavitation erosion. Due to its complexity and dependence on both particle properties and environmental conditions, erosion lacks a unified theoretical explanation. The most widely accepted explanation is the micro-cutting theory, which states that when a particle-laden fluid impacts a solid surface at sufficient velocity, the particles micro-cut the surface, gradually thinning the material. As the fluid continues to flow, the particles repeatedly strike the same regions, creating localized pits on the surface. Solid particles can accumulate in these pits, and if they are corrosive, the wall undergoes chemical attack. The combined effects of erosion and corrosion can ultimately cause perforation, resulting in fluid leakage.

2. Establishment of the Mathematical Model

2.1 Analysis of the Research Object

After passing through heat exchangers F203/1–2, the circulating oil cools below the crystallization temperature of ammonium chloride. Consequently, substantial ammonium chloride crystallizes in the circulating oil, and the high-velocity flow causes erosion and wear on the pipe wall. Owing to space limitations, the 180° outlet bend of E203/1–2 is positioned such that it produces the most significant change in the flow direction of the top circulating oil. Owing to space limitations, the 180° outlet bend of E203/1–2 is positioned such that it produces the most significant change in the flow direction of the top circulating oil. Ammonium chloride crystallization leads to severe erosion in this section of the pipeline. Therefore, this study selects the 180° outlet bend of E203/1–2 as the research object. Its physical structure is shown in Figure 1. Ammonium chloride crystallization causes severe erosion in this section of the pipeline. Consequently, this study focuses on the 180° outlet bend of E203/1–2 as the research object. Its physical structure is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. 180° outlet bend of E203/1–2

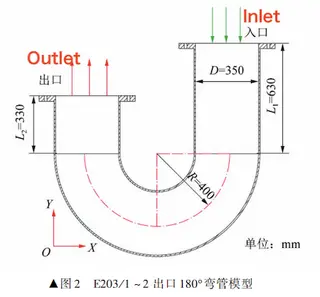

The 180° outlet bend of F203/1–2 is a DN350 standard pipe with a wall thickness of 9 mm and an outer diameter of 377 mm. A pipe model based on these actual dimensions was established, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Model of the 180° outlet bend of E203/1–2

3. Numerical Simulation

3.1 Numerical Simulation Procedure

Given its strong computational capabilities, intuitive operation, and comprehensive physical model library, ANSYS Fluent 2020 is employed in this study to perform the numerical simulations. First, the geometric model is imported into Fluent, where the computational domain, wall boundaries, and inlet and outlet boundaries are defined. The geometry is then processed and meshed. Subsequently, the solver type and corresponding runtime parameters are configured. Next, within the Fluent environment, the physical parameters of the fluid— including governing equations, boundary conditions, velocity, pressure, and density—are specified. The model is then initialized, and the time step and number of iterations are set. Once the calculation converges, the required contour plots, velocity vector fields, post-processing visualizations, and animations are generated.

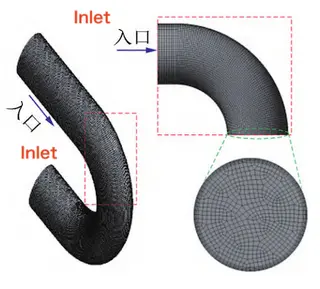

3.2 Mesh Generation

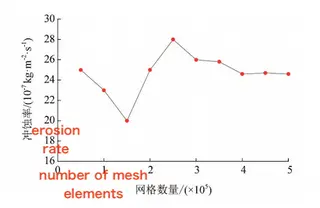

A pipeline model was created in SolidWorks and imported into ANSYS Fluent 2020 via the integrated data interface. The region corresponding to the pipe’s inner cavity was defined as the fluid domain. A multizone meshing strategy was employed to generate the computational mesh, and a mesh independence test was conducted to ensure numerical accuracy and appropriate mesh density. Five layers of mesh refinement were applied near the wall to enhance boundary-layer resolution. The erosion rates obtained under different mesh densities are presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Relationship Between Mesh Density and Erosion Rate

As shown in Figure 3, when the mesh count is below 2.5 × 10⁶, the erosion rate fluctuates markedly and shows no consistent trend. When the mesh count exceeds 2.5 × 10⁶, the erosion rate gradually stabilizes with increasing mesh density. Accordingly, a mesh count of 3 × 10⁶ was chosen for the numerical calculations to ensure sufficient accuracy. The fluid-domain mesh is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4 Meshing model in the fluid domain

3.3 Physical Model and Boundary Conditions

Under the current operating conditions, the top-circulating oil has a flow rate of 615 m³/h, a density of 797 kg/m³, and a dynamic viscosity of 0.015 Pa·s. The inlet flow velocity is 2 m/s. The ammonium chloride crystals suspended in the oil have an average diameter of 0.05 mm, a density of 1.525 × 10³ kg/m³, a chloride-ion concentration of 5.68 mg/L, and an approximate crystallization rate of 10%. For simulation purposes, the salt particles are assumed to move at the same velocity as the circulating oil. Table 1 summarizes the primary physical properties of both the fluid and solid phases.

Table 1. Physical Parameters of the Medium

|

Parameter |

Liquid Phase |

Solid Phase |

|

Flow rate / (m³·h⁻¹) |

615 |

— |

|

Density / (kg·m⁻³) |

797 |

1.525 × 10³ |

|

Velocity / (m·s⁻¹) |

2 |

2 (assumed) |

|

Dynamic viscosity / (Pa·s) |

0.015 |

— |

|

Particle mass flow rate / (kg·s⁻¹) |

— |

0.12 |

|

Particle diameter / (mm) |

— |

0.05 |

After meshing, the Fluent solver was configured for 3D, double-precision calculations, and Fluent was launched to set up the physical models and define all boundary conditions. The top-circulating oil was treated as the continuous phase, while the ammonium-chloride crystals were treated as the discrete phase. The standard k–ε turbulence model was applied to the continuous phase, with physical parameters assigned according to Table 1. As the circulating oil is incompressible, a velocity-inlet boundary of 2 m/s was specified at the inlet, while a pressure-outlet boundary of 1.45 MPa was applied at the outlet. A gravitational acceleration of 9.8 m/s² was applied in the negative Y-direction. The Discrete Phase Model (DPM) was used to track particle trajectories, with the inlet defined as a surface-normal injection and particle velocity set equal to the fluid velocity. Both the inlet and outlet were set to “Escape,” and the pipe wall was defined as a no-slip, reflective boundary for the particle phase.

3.4 Analysis of Calculation Results

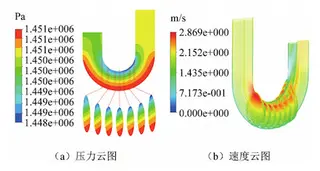

After 355 iterations, the flow-field distribution was obtained, as shown in Figure 5. In the straight inlet section, the circulating oil exhibits relatively uniform pressure and velocity distributions. Upon entering the bend, however, both pressure and velocity vary sharply. The pressure peaks at the outer arc wall of the bend, exhibiting a symmetrical distribution, while the pressure at the inner arc wall of the inlet is lower and gradually rises along the flow direction.

(a) Pressure field contour (b) Velocity field contour

Figure 5. Flow-field distribution

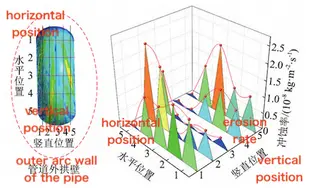

With respect to velocity, the highest flow velocity occurs along the inner arc wall, beginning in the straight inlet section and continuing through the bend to the outlet in a parabolic distribution. The velocity along the outer arc wall is lower and varies more gradually. This behavior is mainly attributed to the centrifugal force acting on the circulating oil as it flows through the bend. The outer arc wall restricts the change in flow direction, causing the fluid to continuously impinge on the pipe wall. This converts part of the fluid’s kinetic energy into pressure energy, leading to a pressure increase along the outer arc. According to the continuity equation, the fluid near the inner arc wall is forced toward the inner side of the bend, reducing the local flow-passage area. To maintain a constant volumetric flow rate, the local velocity increases accordingly, which in turn causes a corresponding decrease in pressure. The erosion-rate contour for the pipe bend is shown in Figure 6. In the straight inlet and outlet sections, the flow direction of the circulating oil and the entrained ammonium-chloride crystals remains parallel to the pipe axis. Therefore, the particles do not impact the wall surface, resulting in a very low erosion rate. However, as the fluid passes through the bend, the abrupt change in flow direction causes the ammonium-chloride particles to repeatedly strike the pipe wall, resulting in severe erosion. The most severe erosion occurs along the outer arc wall, where the affected region extends over a relatively large area. Figure 8 shows the erosion-rate curves at various locations along the outer arc wall, indicating that the middle and side regions experience the most severe erosion. The regions of maximum erosion narrow and converge along the direction of fluid flow. Erosion damages the pipe wall surface, allowing ammonium-chloride crystals to accumulate in the affected areas, which exacerbates localized pitting corrosion. As a result, perforation and leakage are most likely in the middle and lateral regions of the outer arc wall, designating these areas as critical points for routine wall-thickness inspections.

Figure 6 Cloud map of erosion rate distribution

Figure 7. Erosion-rate curves at different positions on the outer arc wall of the bend

4. Analysis of Influencing Factors

4.1 Effect of Inlet Flow Velocity on Erosion Rate

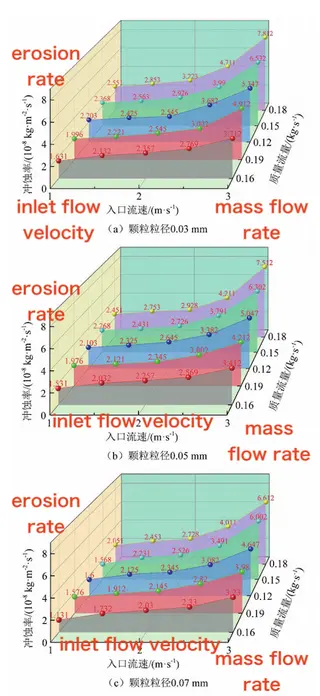

Figure 8 illustrates the erosion rates at various inlet flow velocities, with ammonium-chloride particle mass flow rates ranging from 0.06 to 0.18 kg/s and particle sizes of 0.03 mm, 0.05 mm, and 0.07 mm. A positive correlation is observed between inlet flow velocity and pipe erosion rate: as the inlet velocity increases, particle kinetic energy rises, thereby exacerbating erosion and wear on the pipeline. Moreover, the erosion rate increases relatively slowly within the inlet velocity range of 1–2.5 m/s; however, when the inlet velocity exceeds 2.5 m/s, the erosion and wear become significantly more severe.

(a) Particle size 0.03 mm (b) Particle size 0.05 mm (c) Particle size 0.07 mm

Figure 8. Relationship between flow velocity and erosion rate

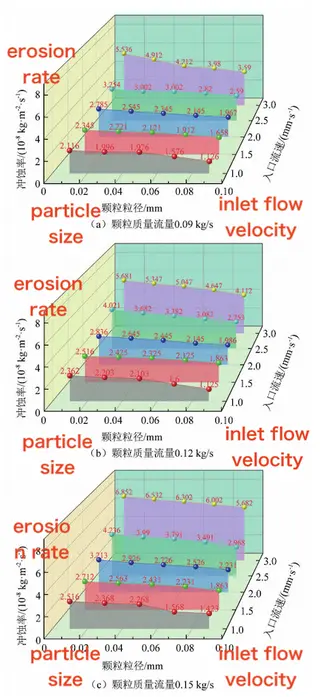

4.2 Influence of Particle Size on Erosion Rate

Under inlet velocities of 1–3 m/s and particle mass flow rates of 0.09, 0.12, and 0.15 kg/s, the effect of particle size on pipeline erosion was studied by varying the particle diameters. Figure 9 illustrates the pipeline erosion rate for particle sizes ranging from 0.01 to 0.09 mm. As shown, at a constant inlet velocity, increasing the particle size results in a decreasing erosion rate across all three mass flow rates. When the particle size ranges from 0.01 to 0.07 mm, the erosion rate decreases gradually; however, once the particle size exceeds 0.07 mm, the erosion rate declines sharply. This phenomenon is mainly due to the strong coupling between small-diameter particles and the fluid, which keeps them well-dispersed and continuously striking the pipe wall, leading to pronounced erosion. In contrast, larger particles have weaker coupling with the fluid and experience more frequent particle–particle collisions, which lowers their individual kinetic energy and, as a result, reduces the erosive impact on the pipeline.

(a) Particle mass flow rate: 0.09 kg/s (b) Particle mass flow rate: 0.12 kg/s (c) Particle mass flow rate: 0.15 kg/s

Figure 9. Relationship between particle size and erosion rate

4.3 Influence of Particle Mass Flow Rate on Erosion Rate

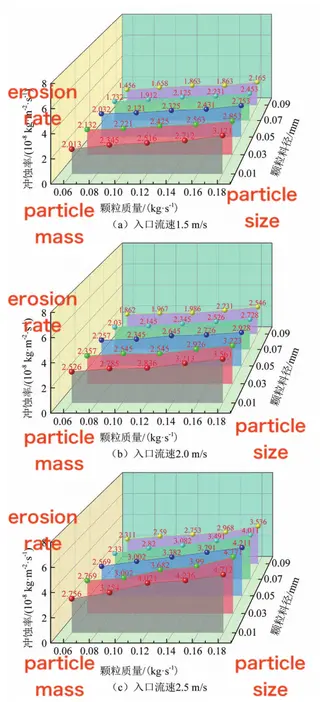

With inlet velocities of 1.5, 2.0, and 2.5 m/s and particle sizes ranging from 0.01 to 0.09 mm, the effect of particle mass flow rate on pipeline erosion was evaluated for 0.06–0.18 kg/s, and the resulting erosion rates are presented in Figure 10.

(a) Inlet velocity 1.5 m/s (b) Inlet velocity 2.0 m/s (c) Inlet velocity 2.5 m/s

Figure 10. Relationship between particle mass flow rate and erosion rate

As illustrated, the erosion intensity increases with the mass flow rate of ammonium chloride particles, and when the particle mass flow rate exceeds 0.09 kg/s combined with an inlet velocity above 2.5 m/s, the erosion rate escalates sharply. At low inlet velocities, increasing the particle mass flow rate mainly raises the number of particles, while their individual kinetic energy remains relatively constant. Consequently, the particle–wall impacts are mild, and erosion remains limited. In contrast, when both the particle mass flow rate and inlet velocity are elevated, the number of particles and their kinetic energy increase simultaneously. Consequently, the solid particles impact the pipe wall more frequently and with higher energy, resulting in significantly intensified erosion.

5. Conclusions

- The maximum flow velocity occurs along the inner arc wall of the pipe inlet, extending toward the outlet in a parabolic profile, whereas the highest pressure is found at the outer arc wall, exhibiting a symmetrical distribution. The lowest pressure occurs at the inner arc wall of the inlet and gradually rises along the flow direction, a pattern primarily resulting from the forced change in the fluid’s flow direction.

- Pipeline erosion is concentrated at the middle and lateral regions of the outer arc wall, covering a relatively large area; the pipe wall at these locations is damaged, and ammonium-chloride salts tend to accumulate, causing localized pitting and potential leakage.

- The pipeline erosion rate rises with increasing inlet flow velocity, becoming particularly pronounced above 2.5 m/s, while larger ammonium-chloride crystal particle sizes correspond to a gradual decrease in erosion. For particle sizes ranging from 0.01 to 0.07 mm, the erosion rate declines moderately, while for sizes exceeding 0.07 mm, the decrease in erosion rate becomes significantly more pronounced. Additionally, the particle mass flow rate significantly influences erosion, and this effect becomes more pronounced at higher inlet velocities.

Send your message to this supplier

Related Articles from the Supplier

Four Methods of Pipeline Connection

- Mar 18, 2016

Pipe Material Application of Pipeline Project

- Jul 13, 2016

The Connection Technology of Fire Pipeline

- Aug 09, 2016

Related Articles from China Manufacturers

Pipeline Ball Valve Technical Requirements

- Apr 18, 2016

Design pressure and design temperature of pipeline

- Mar 10, 2020

Pipeline acceptance standards and correct procedures

- Jun 24, 2020

Pipeline Ball Valve Technical Requirements

- Sep 23, 2016

Related Products Mentioned in the Article

Supplier Website

Source: https://www.landeepipefitting.com/pipeline-erosion-from-ammonium-chloride-crystallization-in-catalytic-cracking-units.html