Static & Dynamic Valve Sealing: A Practical Engineering Guide

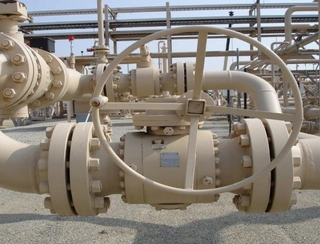

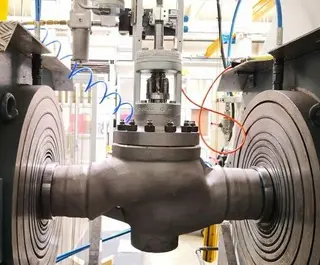

Valves are critical components in industrial piping systems, responsible for controlling the flow of fluids. Among all performance indicators, sealing capability is the most important measure of valve quality. Poor sealing can lead to leakage in the form of seepage, dripping, or spraying, resulting in media loss, environmental pollution, and, in severe cases, safety incidents. For media that are flammable, explosive, toxic, hazardous, or radioactive, any form of leakage is unacceptable. Therefore, a thorough understanding of valve sealing technology is essential for ensuring industrial safety and operational reliability.

Valve sealing technology is broadly divided into two categories: static sealing and dynamic sealing. Static sealing addresses leakage between stationary contact surfaces, while dynamic sealing prevents leakage around moving components, primarily the valve stem. This article explores both aspects in detail, covering technical principles, structural types, and material selection.

Valve Static Sealing: Solutions for Stationary Interfaces

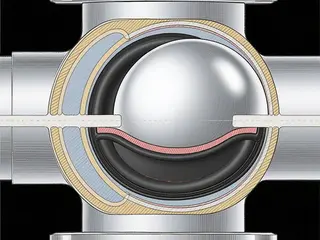

Static sealing refers to the formation of a seal between two non-moving contact surfaces to prevent media from escaping through the joint. It is the most fundamental sealing method in valves and is widely used at connections such as the valve body-to-bonnet joint and flange interfaces. The core element of static sealing is the gasket, which is compressed by bolts to deform and fill surface irregularities, thereby creating an effective seal.

1. Common Gasket Types and Characteristics

- Flat Gaskets: Flat gaskets are the simplest form, consisting of a flat sheet placed between two flange faces. Depending on the material, they can be categorized as plastic, rubber, metal, or composite gaskets. Plastic gaskets offer excellent corrosion resistance but limited temperature tolerance. Rubber gaskets provide strong elasticity but have restricted pressure capacity. Metal gaskets feature high strength and excellent temperature resistance, making them suitable for high-temperature and high-pressure applications. Selection should consider media properties, temperature, and pressure.

- O-Rings: With a circular cross-section, O-rings possess a self-energizing effect. When subjected to media pressure, they are pushed against one side of the groove, enhancing sealing performance compared to flat gaskets. Easy to install and cost-effective, O-rings are widely used in low-pressure, ambient-temperature environments.

- Jacketed Gaskets: Jacketed gaskets are composite structures in which one material is encased within another, typically a metallic shell surrounding rubber or plastic. This design combines the strength of metal with the elasticity and corrosion resistance of the outer layer, delivering superior sealing performance compared to single-material gaskets.

- Special-Shaped Gaskets: These include oval, diamond, serrated, and dovetail designs. Many feature a self-tightening function, meaning sealing performance improves as media pressure increases. They are primarily used in medium- and high-pressure valves; lens gaskets are a common example in high-pressure systems.

- Corrugated Gaskets: Featuring a wave-like structure and often made from combinations of metal and non-metal materials, corrugated gaskets require relatively low bolt preload while still providing excellent sealing. They are particularly suitable for applications where bolt tightening force is limited.

- Spiral Wound Gaskets: Constructed by alternately winding thin metal strips and non-metallic filler materials into a multilayer structure, spiral wound gaskets have a corrugated cross-section. The metal provides strength and temperature resistance, while the filler ensures elasticity and tightness. With excellent resilience and adaptability to temperature and pressure fluctuations, they are among the most widely used gasket types today.

2. Gasket Material Classification and Applications

Gasket materials generally fall into three categories: metallic, non-metallic, and composite.

- Metallic Materials: Common metals include copper, aluminum, low-carbon steel, stainless steel, nickel, and Monel alloys. Their shared advantages are high strength and strong temperature resistance. Lead can withstand only about 100 °C and has limited pressure capability; aluminum tolerates up to 430 °C and pressures around 64 kg/cm²; copper withstands approximately 315 °C; low-carbon steel about 550 °C; silver, nickel, and Monel alloys up to 810 °C; and stainless steel up to roughly 870 °C. Metallic materials are ideal for high-temperature and high-pressure conditions but must be evaluated for corrosion compatibility with the media.

- Non-Metallic Materials: These include rubber, plastics, and asbestos products. Rubber is soft and adaptable, with different formulations offering resistance to acids, alkalis, or oils. Nitrile rubber excels in oil resistance, fluoroelastomers handle high temperatures and chemical exposure, and silicone rubber performs well in low-temperature environments. Plastics such as PTFE provide exceptional corrosion resistance and low friction but have relatively poor elasticity. Asbestos rubber sheets have historically been among the most widely used non-metallic sealing materials, graded by pressure and temperature capacity: gray for low pressure (≤16 kg/cm², 200 °C), red for medium pressure (≤40 kg/cm², 350 °C), purple-red for high pressure (≤100 kg/cm², 450 °C), and green specifically for oil media.

- Composite Materials: Composite gaskets combine the advantages of metals and non-metals. Metal-jacketed gaskets, for example, feature a metallic shell filled with asbestos, PTFE, or fiberglass, offering both durability and elasticity. Spiral wound gaskets are another classic example, achieving performance balance through layered construction.

Valve Dynamic Sealing: Solutions for Moving Components

Dynamic sealing prevents internal media from leaking along the valve stem during operation. Unlike static sealing, it must accommodate relative motion while maintaining tightness and ensuring smooth stem movement, placing higher demands on sealing materials.

1. Stuffing Box Structures

The stuffing box is the most widely used dynamic sealing method and generally comes in two main configurations:

- Gland-Type Stuffing Box: This is the most common design, consisting of a stuffing box body, packing, gland, and compression bolts. Glands may be integral or split; integral designs are simpler, while split designs facilitate installation and maintenance. Compression bolts may be T-bolts, stud bolts, or hinged bolts, selected based on valve pressure and size. This structure provides strong compression and reliable sealing, suitable for most valve applications.

- Compression Nut Type: With a smaller external profile, this design compresses packing directly via a nut. Due to structural limitations, the achievable compression force is lower, so it is typically used in small, low-pressure valves.

2. Packing Material Requirements and Common Types

Packing materials directly contact the valve stem and form the core of dynamic sealing. Ideal packing should provide excellent sealing capability, low friction, resistance to pressure and temperature variations, corrosion resistance, and high wear durability.

Common materials include:

- Rubber O-Rings: Effective in low-pressure, ambient-temperature environments, though natural rubber is generally limited to temperatures below 60 °C.

- PTFE Braided Packing: Made by weaving fine PTFE strips into rope-like structures, offering exceptional corrosion resistance and extremely low friction—ideal for aggressive media and cryogenic conditions.

- Flexible Graphite Packing: A modern sealing material capable of withstanding temperatures up to 1600 °C in inert environments. Its self-lubricating properties make it the preferred packing for high-temperature service.

- Asbestos Packing: A traditional material with good heat and corrosion resistance, typically impregnated with lubricants or other agents to improve sealing. However, its usage is declining due to environmental concerns.

3. Specialized Dynamic Sealing Technologies

For toxic, hazardous, flammable, explosive, or radioactive media, especially in applications requiring zero leakage, bellows sealing technology is often employed. One end of the metal bellows connects to the valve stem and the other to the bonnet, forming a completely enclosed chamber that eliminates the possibility of stem leakage. Bellows seals are frictionless and maintenance-free but come with higher costs and limited stroke, making them suitable mainly for specialized operating conditions.

Fundamental Principles of Valve Sealing

Understanding sealing principles is key to selecting and using sealing components effectively. Leakage occurs primarily due to two factors: the presence of gaps between sealing pairs and pressure differentials across them. Valve sealing can be analyzed from four perspectives: liquid sealing behavior, gas sealing behavior, leakage pathways, and sealing surface characteristics.

1. Liquid Sealing Principles

Liquid sealing depends on viscosity and surface tension. When a leakage capillary contains gas, surface tension can either repel or attract the liquid, forming a contact angle. If the angle is less than 90°, the liquid is drawn into the capillary, causing leakage; if greater than 90°, the liquid is repelled. However, surface films such as grease or wax can dissolve and alter surface properties, allowing previously repelled liquids to wet the surface and leak.

According to Poiseuille's law, reducing capillary diameter and increasing fluid viscosity can minimize leakage. This explains why higher-viscosity fluids are generally easier to seal.

2. Gas Sealing Principles

Gas sealing relates to molecular characteristics and viscosity. Leakage is inversely proportional to capillary length and gas viscosity but directly proportional to capillary diameter and driving force. When the capillary diameter approaches the mean free path of gas molecules, they flow freely through thermal motion.

Notably, even if plastic deformation reduces capillary size below molecular dimensions, gas can still diffuse through metal walls. Consequently, gas sealing requirements are stricter than those for liquids, and gas test standards are typically higher. This is why water may provide an effective seal during testing, whereas air may not.

3. Sealing Surface Characteristics

Valve sealing surfaces exhibit both roughness (microscopic irregularities) and waviness (larger undulations). When elastic strain in metal is limited, compression must exceed the elastic limit to induce plastic deformation and achieve sealing.

Initially, only surface asperities make contact, and small loads can plastically deform them. As load increases, the contact area expands, transitioning from plastic to elastoplastic deformation. Complete sealing occurs only when the load is sufficient to cause substantial plastic deformation in the underlying material, allowing surfaces to conform along continuous lines and circumferential paths.

For this reason, sealing pairs are often designed with a controlled hardness difference so coordinated plastic deformation under pressure improves sealing performance.

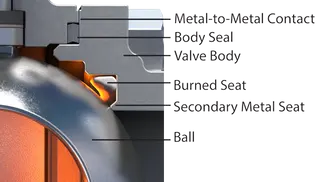

4. Damage and Protection of Sealing Pairs

The sealing pair, formed by the valve seat and closure element, is vulnerable to corrosion, abrasive particles, cavitation, and erosion.

Particle size is especially important. If particles are smaller than surface irregularities, they may improve surface finish during run-in; if larger, they can scratch the sealing surface and reduce accuracy. Therefore, abrasive media require wear-resistant materials or filtration.

Material selection must balance corrosion resistance, scratch resistance, and erosion resistance. Weakness in any one property can significantly degrade sealing performance—for example, corrosion-resistant but soft materials may wear quickly in particle-laden media, while wear-resistant materials with poor corrosion resistance may fail in aggressive environments.

Key Considerations for Valve Seal Selection

Choosing the correct sealing type and material is essential for valve performance. Important factors include:

- Media Characteristics: Highly corrosive media call for PTFE, fluoroelastomers, or Hastelloy; particle-laden media require hard alloys; toxic or hazardous media benefit from high-reliability designs such as bellows seals.

- Temperature Range: Flexible graphite and metal gaskets suit high temperatures; specialized rubbers or PTFE are ideal for low temperatures; spiral wound gaskets perform well where temperatures fluctuate.

- Pressure Rating: Non-metallic materials are adequate for low pressure; asbestos rubber or composite gaskets for medium pressure; metal gaskets and lens rings for high pressure; ultra-high pressure often demands metal-to-metal sealing.

- Cost-Effectiveness: Evaluate both initial cost and service life. Higher-priced materials that significantly extend maintenance intervals may offer better long-term value.

Conclusion

Although valve sealing technology may appear straightforward, it integrates knowledge from fluid mechanics, materials science, and mechanical design. Static sealing relies on gaskets to secure stationary interfaces, while dynamic sealing uses stuffing boxes and packing to prevent leakage at moving parts. A solid grasp of liquid and gas sealing principles, along with material characteristics and application ranges, enables informed engineering decisions.

As industry evolves, sealing requirements continue to rise. Advanced materials such as flexible graphite and high-performance engineering plastics, along with innovations like bellows seals and liquid gasket compounds, provide more effective solutions than ever before. Yet the fundamental principles remain unchanged: eliminate gaps, block leakage paths, and adapt to operating conditions. Only by understanding these fundamentals can engineers apply sealing technologies effectively and ensure safe, reliable valve operation.

During selection and operation, it is advisable to consult professional sealing manufacturers to develop optimal solutions tailored to specific working conditions. Equally important are proper installation, routine inspection, and timely replacement of sealing components. Together, these practices allow valves to deliver their full sealing performance and support the long-term, safe, and stable operation of industrial systems.

Send your message to this supplier

Related Articles from the Supplier

Related Articles from China Manufacturers

What are Dynamic and Static Seals in Valve Systems?

- Apr 28, 2025

The Static Sealing of the Valve

- Sep 15, 2021

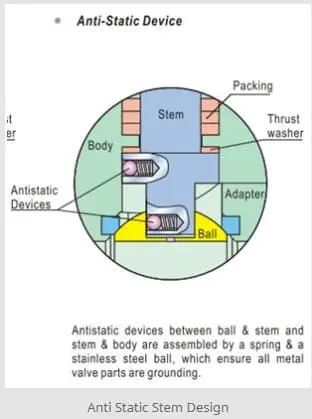

The Anti-Static Device of Ball Valves

- Mar 18, 2019

Related Products Mentioned in the Article

Zhejiang Kosen Valve Co., Ltd.

- https://www.kosenvalve.com/

- Business Type: Industry & Trading, Manufacturer,

Supplier Website

Source: https://www.kosenvalve.com/media-hub/static-dynamic-valve-sealing-a-practical-engineering-guide.html