Heat Treatment Processes for Martensitic Stainless Steel Forgings

In modern industries such as petrochemicals, precision mold manufacturing, aerospace engineering, power generation, and high-end equipment manufacturing, material selection is often a decisive factor in determining product reliability, service life, and overall performance. Among the many classes of metallic materials used in these demanding fields, martensitic stainless steel occupies a uniquely important position.

From steam turbine blades and rolling bearings to plastic molds, valve stems, pump shafts, and other precision components operating in corrosive or high-stress environments, martensitic stainless steel forgings are widely used due to their excellent combination of strength, hardness, wear resistance, and moderate corrosion resistance. However, these properties do not arise naturally in the as-forged condition. Instead, they are the result of carefully designed and strictly controlled heat treatment processes.

This article presents a comprehensive and systematic discussion of the heat treatment technology for martensitic stainless steel forgings, explaining the metallurgical principles behind each step and offering practical guidance for industrial applications. By understanding and mastering this “metallic alchemy,” engineers and technicians can achieve the optimal balance between corrosion resistance, mechanical strength, hardness, and toughness.

What Is Martensitic Stainless Steel?

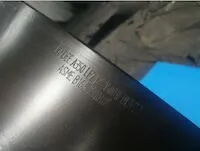

Martensitic stainless steel is a class of chromium-containing alloy steel, typically with a chromium content between 12% and 14%, combined with varying amounts of carbon and, in some grades, additional alloying elements such as nickel or molybdenum. Unlike austenitic stainless steels (such as AISI 304 or 316) and ferritic stainless steels, martensitic stainless steels are distinguished by their ability to be strengthened through heat treatment.

This characteristic makes martensitic stainless steel fundamentally different from other stainless steel families. In simple terms, it behaves like a “transformer.” When heated to sufficiently high temperatures (generally 950–1100°C), its microstructure transforms into austenite, a face-centered cubic phase capable of dissolving significant amounts of carbon. When this austenite is rapidly cooled through quenching, it transforms into martensite, a supersaturated, body-centered tetragonal structure characterized by very high hardness and strength.

This phase transformation mechanism allows martensitic stainless steel to combine several desirable properties:

- Load-bearing capacity comparable to structural alloy steels

- High hardness and wear resistance similar to tool steels

- Basic corrosion resistance provided by chromium-rich passive films

Thanks to this three-in-one performance profile, martensitic stainless steel is widely used for components that must operate under mechanical load, friction, and corrosive exposure simultaneously. Typical applications include plastic molds, plungers, springs, bearings, pump components, valve stems, turbine parts, and various precision mechanical elements.

The Fundamental Rule of Heat Treatment

When designing and executing heat treatment processes for martensitic stainless steel forgings, there is one principle that must never be violated:

Any heat treatment process must preserve, and ideally enhance, the corrosion resistance of the material.

The corrosion resistance of martensitic stainless steel depends primarily on the presence of sufficient chromium in solid solution within the steel matrix. Chromium enables the formation of a dense, stable chromium oxide passive film on the surface, which acts as a barrier against corrosive media.

Improper heat treatment can severely compromise this protective mechanism, leading to several detrimental effects:

- Chromium depletion: Excessive precipitation of chromium carbides (e.g., Cr₃C₂, Cr₇C₃) reduces the chromium content of the matrix

- Surface degradation: Oxidation, decarburization, or carburization during heating damages surface integrity

- Harmful phase formation: Prolonged exposure to inappropriate temperature ranges can cause brittle or corrosion-prone phases to precipitate

For this reason, strict control of the furnace atmosphere is essential. Protective atmospheres, vacuum furnaces, or controlled gas environments are often used to prevent oxidation and carbon exchange at the surface.

For complex-shaped or high-precision components, alternative materials such as precipitation-hardening martensitic stainless steels (e.g., 17-4PH) may be selected. These steels allow machining in a relatively soft condition, followed by aging heat treatment to achieve final strength, thereby minimizing distortion and dimensional instability.

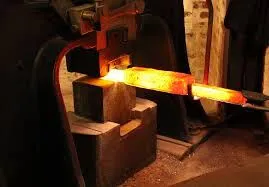

Quenching of Martensitic Stainless Steel Forgings

After establishing corrosion resistance as a non-negotiable requirement, the next focus is quenching, which is the core step responsible for developing the martensitic structure. The success of quenching depends on two key factors: accurate temperature control and appropriate cooling methods.

1. Selection of Quenching Temperature

Different grades of martensitic stainless steel require different quenching temperatures to achieve optimal properties.

High-Carbon, High-Chromium Grades

- (e.g., 95Cr18, 9Cr18)

- These steels contain relatively high carbon content and are primarily used for applications demanding extreme hardness and wear resistance, such as bearings and cutting tools.

- Typical quenching temperature: 1050–1100°C

- If the temperature is too low, carbides will not fully dissolve, reducing both hardness and corrosion resistance. If the temperature is too high, excessive δ-ferrite and retained austenite may form, degrading mechanical performance and dimensional stability.

Medium-Carbon, High-Chromium Grades

- (e.g., 40Cr13, 2Cr13)

- These are the most widely used martensitic stainless steels for general corrosion-resistant structural components.

- Typical quenching temperature: 1000–1050°C

- 40Cr13 steel exhibits good hardenability, allowing small or simple parts to be air quenched, which significantly reduces the risk of distortion and cracking.

Low-Carbon, High-Chromium Grades

- (e.g., 14Cr17Ni2, 1Cr17Ni2)

- With approximately 2% nickel addition, these steels exhibit improved corrosion resistance compared with 40Cr13.

- Typical quenching temperature: 950–1050°C or 980–1000°C

Ultra-Low Carbon Grades

- (e.g., 1Cr13, ≤0.15%C)

- Typical quenching temperature: 950–1050°C

- Heating occurs in the austenite + ferrite two-phase region

- Final microstructure after quenching consists of martensite + ferrite

2. Selection of Cooling Methods

Although quenching is often perceived simply as “rapid cooling,” the choice of cooling medium plays a decisive role in determining final quality.

Common cooling methods include:

Oil quenching: Most commonly used; moderate cooling rate and good crack resistance

- Air cooling: Suitable for small, simple components; minimizes distortion

- Hot oil quenching (100–150°C): Gentler than cold oil; suitable for complex geometries

- Martempering: Holding in salt bath or hot oil before final cooling

- Austempering: Isothermal transformation to lower bainite for superior combined properties

It is particularly important to note that martensitic stainless steels are sensitive to thermal cracking. Their relatively low thermal conductivity at low temperatures makes them prone to internal stress concentration. Rapid heating, especially for large or complex forgings, can easily cause distortion or cracking.

Therefore, slow heating, preheating, or stepwise temperature ramping must be applied to ensure uniform temperature distribution throughout the component.

Tempering of Martensitic Stainless Steel Forgings

After quenching, martensitic stainless steel exhibits extremely high hardness but also high internal stress and brittleness. Tempering is mandatory and must be performed as soon as possible after quenching.

A critical guideline is that the tempering temperature must be higher than the service temperature, otherwise further microstructural changes may occur during operation, leading to instability and stress accumulation.

1. Low-Temperature Tempering (200–370°C)

Low-temperature tempering is used when maximum hardness and wear resistance are required.

Typical examples include:

- 95Cr18 steel: ~200°C

- 40Cr13 (high hardness requirement): 200–300°C

- 14Cr17Ni2: 250–300°C, producing tempered martensite with high strength and corrosion resistance

Low-temperature tempering relieves part of the quenching stress while retaining high hardness. However, excessive tempering promotes chromium carbide precipitation, reducing corrosion resistance and wear performance.

2. High-Temperature Tempering (600–750°C)

High-temperature tempering is applied when components require the best combination of strength, ductility, and toughness.

- Typical conditions include:

- 40Cr13 (high toughness requirement): 650–700°C

- 14Cr17Ni2: 600–700°C, resulting in tempered sorbite and banded ferrite

An important benefit of high-temperature tempering is the transformation of chromium carbides into (Cr,Fe)-type carbides, which reduces chromium-depleted zones and improves corrosion resistance.

However, 40Cr13 steel is prone to temper embrittlement. After high-temperature tempering, oil cooling is recommended to mitigate this effect.

3. The Forbidden Tempering Zone (370–600°C)

Tempering in the 370–600°C range, particularly between 400–600°C, must be strictly avoided.

In this temperature range:

- Impact toughness decreases sharply due to temper embrittlement

- Corrosion resistance deteriorates significantly

- For 14Cr17Ni2 steel, prolonged exposure at 450–500°C causes severe embrittlement and corrosion degradation

The practical rule is clear:

- Below 370°C: preserve hardness

- Above 600°C: improve toughness

- Never temper in the intermediate range

Special Treatment Techniques

For extreme service conditions or precision manufacturing, conventional quenching and tempering may not be sufficient. Advanced treatment techniques are often employed.

1. Nitriding

After quenching and low-temperature tempering, nitriding can be applied to improve surface hardness and wear resistance. A hard nitride layer forms on the surface while maintaining corrosion resistance.

Typical temperature: 500–580°C

Low distortion and excellent dimensional stability

2. Precipitation Hardening

For complex and dimensionally sensitive components, precipitation-hardening martensitic stainless steels such as 17-4PH are ideal.

Solution treatment at ~1050°C, water quenched

Aging treatment at 480–620°C

This approach achieves high strength with minimal distortion.

3. Annealing for Softening

When machining is required and hardness is too high, annealing is used.

Low-carbon steels: 750–800°C air cooling, or controlled slow cooling for lower hardness

Medium/high-carbon steels: high-temperature tempering or full annealing

Annealed martensitic stainless steel exhibits reduced mechanical strength and corrosion resistance and is suitable only for low-performance applications or as a pre-machining condition.

Conclusion

The heat treatment of martensitic stainless steel forgings is a precise and highly disciplined metallurgical process. It requires engineers to carefully balance corrosion resistance, strength, hardness, and toughness through proper selection of quenching temperatures, cooling methods, and tempering regimes.

By strictly controlling heat treatment parameters and avoiding critical temperature zones, martensitic stainless steel components can deliver long-term, reliable performance even in harsh corrosive environments.

Every heating and cooling cycle reshapes the internal microstructure of the metal. Only through a deep understanding of material behavior and disciplined process control can the dual advantages of martensitic stainless steel, stainless and strong, be fully realized in high-quality engineering components.

Send your message to this supplier

Related Articles from the Supplier

Heat Treatment Process of Stainless Steel Forgings

- Jul 25, 2024

Vacuum Heat Treatment Used for Mold

- Jan 15, 2016

Common Misunderstanding of Heat Treatment

- Aug 14, 2024

Quenching Process by Remaining Heat from Forging

- Jun 16, 2015

Related Articles from China Manufacturers

Copper Forging Processes and Heat Treatment

- Jan 14, 2026

The Heat Treatment Process of Steel Pipes

- Jul 05, 2017

The Heat Treatment Process of Cold Drawn Steel Pipes

- Oct 17, 2021

Effect of Heat Treatment on Die-cast Aluminum Alloys

- Jun 24, 2024

Related Products Mentioned in the Article

Supplier Website

Source: https://www.forging-casting-stamping.com/heat-treatment-processes-for-martensitic-stainless-steel-forgings.html