Forged Component Hardness: Key Factors and Optimization

In modern industrial production, forged components are widely used in the manufacturing of various complex and high-demand mechanical parts due to their outstanding mechanical properties. Hardness, as one of the key performance indicators of forged components, has a crucial impact on the overall performance of the product. This article will explore in depth the knowledge related to the hardness of forged components, including the factors affecting hardness, hardness testing methods, and how to improve hardness through process optimization, to help readers better understand the importance of forged component hardness and its application in actual production.

Hardness of Forged Components

Hardness refers to the ability of a material to resist indentation by an external force. It is an important indicator for measuring the softness or hardness of metal materials. For forged components, hardness not only directly affects their wear resistance and service life but is also closely related to other mechanical properties such as strength and toughness. Generally, forged components with higher hardness usually have better wear resistance and strength, but excessively high hardness may reduce plasticity, affecting their machinability and impact resistance.

Mechanism of Hardness Formation during Forging

Effect of deformation parameters on hardness: During the forging process, controlling parameters such as the amount of deformation, deformation speed, and deformation temperature can significantly change the metal's grain structure and dislocation density, thereby affecting the product's hardness. Larger deformation amounts and higher deformation speeds can make the metal grains finer and increase dislocation density, thus improving the product's strength and hardness. This is because finer grains can hinder the movement of dislocations, making it more difficult for the metal to undergo plastic deformation under external forces, thereby exhibiting higher hardness.

Effect of heat treatment on hardness: Forged metal products usually require heat treatment to further improve strength and hardness. Common heat treatment processes include quenching, tempering, and normalizing. Quenching rapidly cools the metal to form a harder martensitic structure, significantly increasing the product's hardness. However, although quenched metal has high hardness, it is also relatively brittle, so tempering is usually required. Tempering and normalizing can, through appropriate heating and holding, transform martensite partially or fully into tougher bainite, cementite, and pearlite structures, improving the product's toughness and strength. By reasonably selecting heat treatment process parameters, a good balance between hardness and toughness can be achieved to meet the requirements of different application scenarios.

Hardness Characteristics of Different Metal Materials

Different metal materials have different mechanical properties and heat resistance, so when selecting forging materials, it is necessary to consider the specific application scenarios and requirements. Generally, metals with high strength and hardness can provide better product performance. For example, carbon steel and alloy steel are commonly used forging materials. Through the addition of different alloying elements and heat treatment processes, different hardness and strength requirements can be achieved. Carbon steel has good machinability and certain strength, suitable for general mechanical part manufacturing; while alloy steel can further improve hardness and strength by adding alloying elements such as chromium, nickel, and molybdenum, suitable for parts with higher performance requirements, such as crankshafts and connecting rods of automobile engines.

Hardness Testing Methods for Forged Components

Mechanical performance is the most important performance indicator of forged components, and hardness testing is a key step in evaluating forged component quality. Almost all forged components require tensile testing, and most forged components require Brinell hardness testing. Machined and heat-treated workpieces undergo Rockwell hardness testing. If the workpiece is too large for Rockwell testing, Shore or Leeb hardness testing can be used instead.

1. Brinell Hardness Test

The Brinell hardness test is one of the most commonly used methods for testing the hardness of forged components. It presses a hardened steel or carbide ball of a certain diameter into the surface of the metal under a specified load and maintains it for a prescribed time, then removes the load and measures the diameter of the indentation on the sample surface to calculate the hardness value. The advantages of the Brinell hardness test are its simplicity of operation and applicability to metal materials across a wide hardness range, providing a relatively accurate reflection of material hardness. However, for large workpieces or rough surfaces, the Brinell hardness test may have certain limitations.

2. Rockwell Hardness Test

The Rockwell hardness test is another commonly used hardness testing method, especially suitable for machined and heat-treated workpieces. It determines hardness by measuring the depth of penetration of the indenter into the metal surface. The advantages of the Rockwell hardness test are its simple operation, fast measurement speed, and applicability to metal materials across a wide hardness range. It is especially accurate for small workpieces and smooth surfaces. However, it may not be suitable for large workpieces or materials with relatively low hardness.

3. Shore Hardness Test and Leeb Hardness Test

For large workpieces or situations where Rockwell testing cannot be performed, Shore or Leeb hardness tests can be used. The Shore hardness test determines hardness by measuring the rebound height of an elastic rod, suitable for large workpieces and rough surfaces. The Leeb hardness test determines hardness by measuring the ratio of the rebound velocity to the impact velocity of an impact body. It is simple to operate, has a wide measurement range, and is suitable for all types of metal materials, especially large workpieces and on-site testing.

Effect of Work Hardening on Forged Component Hardness

Work hardening refers to the phenomenon where, with increasing cold deformation, the strength and hardness of metal materials increase while plasticity and toughness decrease. This is a very important strengthening method, used to improve the strength and hardness of forged materials, especially for alloy forgings that cannot be strengthened by heat treatment. For example, cold-rolled steel sheets have higher strength and hardness than hot-rolled steel sheets, mainly due to work hardening.

1. Factors Affecting Work Hardening

The degree of work hardening is influenced by multiple factors. Greater cutting force and plastic deformation lead to higher hardening levels and deeper hardened layers. Therefore, increasing feed rate and cutting depth while reducing rake angle increases cutting force, making work hardening more pronounced. Heat generated during cutting can soften the surface hardened layer, so higher cutting temperatures increase recovery of the hardened layer. When deformation speed is fast, contact time is short and plastic deformation is insufficient, reducing hardening. Low-hardness, high-plasticity materials exhibit more severe surface work hardening during machining.

2. Advantages and Disadvantages of Work Hardening

Work hardening is beneficial for ensuring uniform plastic deformation in forged components because areas deformed first are strengthened, and subsequent deformation occurs mainly in undeformed areas, allowing the material to deform evenly. For example, in processes such as wire drawing or deep drawing of cylindrical forgings, work hardening ensures uniform material deformation. Work hardening also enhances the operational safety of metal parts and components. For instance, if a part experiences stress exceeding its yield point during operation, minor plastic deformation occurs, but the increased yield strength from work hardening may prevent further deformation or fracture.

However, although work hardening increases strength, it reduces plasticity, which can complicate processes requiring large deformations. For example, during significant diameter reduction in wire drawing, multiple passes with intermediate annealing are needed to restore ductility for further reduction. Materials sensitive to work hardening, such as high-manganese steel, are difficult to machine due to this effect.

Optimizing Forging Processes to Improve Hardness

To enhance the hardness and overall performance of forged components, optimizing forging process parameters is crucial. By reasonably controlling temperature, cooling speed, and forging speed during the forging process, defects and stress concentrations can be minimized, thereby improving product strength and hardness.

1. Temperature Control

During forging, temperature is an important factor affecting hardness. Proper forging temperature ensures sufficient plastic deformation while preventing excessive grain growth. Excessively high temperatures may coarsen grains and reduce hardness, while excessively low temperatures hinder plastic deformation and may cause defects. Therefore, precise control of forging temperature is required based on different metals and process requirements to achieve desired hardness and strength.

2. Cooling Speed Control

Cooling speed also has a significant impact on forged component hardness. Rapid cooling promotes martensite formation, increasing hardness; slower cooling favors bainite, pearlite, or other structures, enhancing toughness and strength. In production, choosing the appropriate cooling medium and method can control the cooling speed to achieve the desired hardness. For example, during quenching, different media such as oil, water, or air produce different cooling rates and resulting hardness and microstructures.

3. Forging Speed Control

Forging speed is also an important factor affecting hardness. Faster forging increases deformation, refines grains, and increases dislocation density, improving hardness. However, excessively fast forging may cause internal stress concentrations and defects, affecting product quality. Therefore, forging speed must be reasonably controlled according to the specific process and material characteristics to achieve an optimal balance between hardness and quality.

Conclusion

The hardness of forged components is one of their important performance indicators and has a crucial impact on overall product performance. By controlling deformation parameters during forging, optimizing heat treatment processes, and reasonably selecting metal materials, the hardness and overall mechanical properties of forged components can be effectively improved. Accurate hardness testing methods are also a key step in ensuring forged component quality. In actual production, it is necessary to comprehensively consider hardness, strength, toughness, and machinability according to specific application scenarios and requirements, and select suitable forging processes and materials to manufacture high-quality forged components that meet requirements.

Send your message to this supplier

Related Articles from the Supplier

Related Articles from China Manufacturers

Advantages of Forged Components Over Cast Ones

- May 22, 2019

Essential Quenching Techniques for Forged Components

- Oct 17, 2024

Forged Aluminum Components for Motorcycles

- Apr 26, 2024

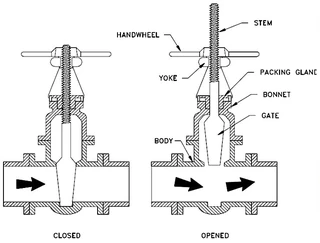

Common Types of Forged Steel valves

- Oct 18, 2016

Precautions for Forged Steel Valves

- Mar 21, 2024

Related Products Mentioned in the Article

Supplier Website

Source: http://www.creatorcomponents.com/news/forged-component-hardness-key-factors-and-optimization.html